As I have mentioned 11 times previously, I am preparing a monograph on the rate of wrongful conviction. Each chapter will deal with one estimate of that rate, beginning with zero and ending beyond 10%. I am posting the draft chapters here, as I write them. I have so far posted the following:

Chapter 0.027: The Scalia Number

Chapter 0.5: The Huff Number

Chapter 0.8: The Prosecutor Number

Chapter 1.0: The Rosenbaum Number

Chapter 1.3: The Police Number

Chapter 1.4: The Poveda NumberChapter 1.9: The Judge Number

Chapter 2.3: The Gross Number

Chapter 3.3: The Risinger Number

Chapter 5.4: The Defense Number

Chapter 8.4: A Skeptical Juror Number

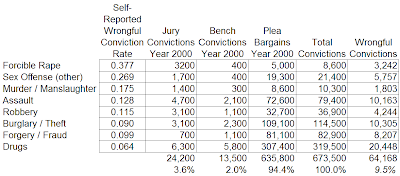

This post presents my estimate for the wrongful conviction rate associated with those who have plea-bargained their way behind bars. Because plea bargains account for 94% of all convictions, and because no other estimate attempts to quantify the wrongful rate of plea bargains, this chapter is important to anyone attempting to understand our overall wrongful conviction rate.

Chapter 9.5

The Inmate Number

The Inmate Number

There is one segment of our society that, as a group, actually knows our country’s rate of wrongful convictions. That segment consists of the 2.5 million people we have behind bars. We may find them to be the most disreputable segment of our society, but perhaps we might learn something if we bothered to ask them.

In 1978 and ’79, the RAND Corporation bothered to ask. They surveyed 2190 jail and prison inmates from California, Michigan, and Texas. Participation was voluntary and conducted independently of jail and prison officials. Each participating inmate filled out an extensive questionnaire requiring approximately 50 minutes to complete. They were paid $5 for their participation. They answered questions regarding their demographics, current conviction, and criminal history. Though the surveys were intended to collect data on career criminals for policy review and recommendations, two questions from the questionnaire are useful for those attempting to calculate wrongful conviction rates.

"What charge(s) were you convicted of that you are serving time for now? (Check all that apply)"Each question was followed by a list of 15 offenses and an “Other” option. Significantly, the last question included a “Did no crime” option. Those who truthfully selected that option claim to have been wrongfully convicted.

“For these convictions, what crimes, if any, do you think you really did? (Check all that apply)."

Tony Poveda, whom you may remember from “Chapter 1.4: The Poveda Number”, summarized the results for the prisoners surveyed, but not for the jail inmates. I present his tabular summary below.

The numbers are revealing in several regards. First, they immediately contradict the myth that, based on claims of inmates, there are no guilty people in prison. Most inmates readily acknowledge their guilt. Almost 95% of those convicted of drug possession concede they were properly convicted.

The second revelation is that the inmate claims of innocence are heavily dependent on the nature of the crimes. While 90% of those convicted of burglary concede their guilt, only 62% of those accused of rape do so.

The third revelation is that the inmate number for wrongful conviction far exceeds those guessed at by police, prosecutors, judges, and defense attorneys. The inmate number substantially exceeds those numbers calculated by those who divide exonerations by convictions. For the astute among you, however, for those of you who pay attention to chapter numbering, the inmate number is lower than four estimates to follow.

The salient question is whether the inmates responded truthfully and accurately. Most people will automatically assume the inmates were not truthful. While society accepted without question their guilty pleas, since 94% of them were convicted based on plea bargains, society is loath to believe their claims of innocence. The societal assumptions, however, are based on nothing more than bias and an unquestioned sense of omniscience. No evidence or analysis is brought forth to explain or defend the different standards for accepting claims of guilt and innocence.

Those who conducted the inmate survey, however, applied precautions common to professional pollsters. Whether conducting presidential tracking polls, taking a census of the entire U.S. population, evaluating customer opinion of a new razor, or asking inmates if they are in fact guilty, professional pollsters use multiple techniques to determine whether or not they are being given reliable data.

One technique for detecting untruthful and inaccurate answers is asking for essentially the same information in different fashions at different points in the questionnaire. Another is to re-interview the same group of people at a later date, to see if they are persistent in their responses. The RAND folks applied both techniques during their inmate survey. They also cross-checked the inmate responses, where possible, against prison records.

After assessing the accuracy of the inmates’ response, the researchers concluded that “83 percent of respondents tracked the questionnaire with a high degree of accuracy and completeness, and were very consistent in their answers.” Also, though the researchers expected the inmates to suppress unfavorable information, they discovered just the opposite: “We found evidence that respondents usually reveal more arrests and convictions in questionnaires or interviews than can be found in official records.”

One explanation for the inmate accuracy, at least as assessed by the researchers, is that the inmates are being truthful for pragmatic rather than lofty reasons. Most inmates are eligible for parole, and I presume most inmates prefer to be released early rather than serve their full term. Maintaining innocence is a pretty good way to insure that you won’t be paroled.

Parole boards consider complete acceptance of responsibility to be a critical issue in rehabilitation. In their belief regarding the power and necessity of confession, parole boards think in the same fashion as many religions, as Alcoholics Anonymous, and as many psychologists. Those who deny their guilt are unrepentant, uncured, and likely to repeat their crimes.

Tom Hutchinson, spokesman for the U.S. Parole Commission, explains that an expression of remorse is a requirement for parole. "It gets dicey when a person expresses innocence -- you can't accept responsibility for it when it's something you say you never did."

Calvin Johnson was convicted of rape by the people of Georgia. In his book Exit To Freedom, he writes:

I am innocent. I have filed appeals at every level, and as always I am denied. The parole board sends smiling representatives who give me hope, but during my hearings they ask me over and over again, "What can you tell us about the crime?" Each time I go up, I am denied parole, and rather than shortening the period between hearings, they lengthen it. Everyone urges me to join the Sex Offenders Program, but membership requires a detailed admission of my crimes.After 16 years in prison, Calvin Johnson became the first man in Georgia freed by DNA evidence.

Arthur Whitfield, convicted of rape by the people of Virginia, was denied parole 14 times during his 23-year incarceration. He was eventually freed after DNA testing conclusively excluded him as the rapist.

Kevin Green, convicted by the people of California for the murder of his unborn child, was denied parole 4 times, in part because he would not admit his guilt. He was eventually freed after DNA proved another man beat Kevin’s wife so severely that she prematurely delivered a nearly-full-term, stillborn child.

Thomas Doswell, convicted of rape by the people of Pennsylvania, was denied parole 4 times over 18 years, in part because he would not admit his guilt. He was eventually freed after DNA testing conclusively excluded him as the rapist. Doswell, incidentally, was picked from a photo lineup by two witnesses after the Pittsburgh police added the letter “R” for “rapist” to the bottom of his photo.

Inmates absolutely understand the risk of maintaining their innocence. Though the results were officially confidential, each questionnaire included an identifier to allow RAND to conduct follow-up surveys by matching the inmate to the identifier. I doubt many inmates who declared themselves innocent on the survey shared that claim with the parole board. I wonder if some inmates refused to declare themselves innocent for fear that the parole board would learn of the specific results.

Not only did the confidential nature of the survey remove the penalty for declaring innocence, it also removed any substantive benefit for doing so. If the confidentiality were maintained, no penalty or benefit would accrue from denying guilt. The confidential nature of the survey seems to be a necessary, if not a sufficient condition for truthful results.

Further evidence that inmates’ self-reports are accurate will be presented in several of the remaining four chapters. For now, we need to look more closely at the results.

<<>>

I re-categorized the inmate data slightly, to allow comparison with later estimates, and I weighted the results by total state-court convictions for year 2000. I present the results below.

The number at the lower right, 9.5%, is the wrongful conviction rate based on prisoner self-reported claims of actual innocence. Assuming the inmate self-reports to be accurate, that number properly accounts for the range of crimes shown. It also accounts for the type of conviction, whether it be by jury trial, bench trial, or plea bargain.

Assuming results from California, Texas, and Michigan can be extrapolated to other states, the 9.5% number is the most comprehensive, all-inclusive number discussed to so far. If it is correct, one need only multiply it by the total number of people incarcerated to obtain an accurate accounting of all people wrongfully behind bars in our country.

No other number discussed so far, and no other number remaining to be discussed, provides a quantitative assessment of the wrongful conviction rate for those who plea-bargained their way behind bars. Since 94% of those behind bars are there as a result of a plea bargain, as shown in the table above, any number not accounting for wrongful guilty pleas cannot properly be applied to our entire prison and jail population.

Assuming that 9.5% number is applicable to the 2.5 million people we now have incarcerated, it means we are now holding 237,500 of our fellow Americans behind bars, despite their innocence.

ERRATA:

The title of the post and the draft chapter number has been adjusted to reflect my most current calculation of a 9.5% wrongful conviction rate based on inmate self-reporting.

ERRATA:

The title of the post and the draft chapter number has been adjusted to reflect my most current calculation of a 9.5% wrongful conviction rate based on inmate self-reporting.

1 comment:

Plea bargains are not JUSTICE...plea bargains allow the district attorney and the court and the under-qualified court appointed lawyer to lessen their case loads. The DA will ask for maximum sentences for those who dare declare innocence and ask for a trial...even though while plea bargaining will agree to a lesser sentence. So, they get some people who are actually guilty to plea out and be punished, they also catch many who are innocent to plea just because of the threat of a harsh sentence. The court appointed lawyer is kind of in the dark at this point because they have no idea yet of what the prosecutor has for evidence. Discovery only comes into play at trial. Also, DNA evidence is routinely denied due to Prosecution and Judicial adversity. Judges are supposed to be impartial, but many have been prosecutors before being judges. DNA should be tested in EVERY case...especially those on appeal. But until we, the people, hold the justice system itself accountable for those who have been exonerated, it will not change. We, taxpayers, are responsible to pay for those wrongfully convicted...those who convicted them are exempt.

Post a Comment