This morning, I saw an article about Google changing their ranking algorithm. "Websites to Google:" blared the headline. "You're killing our business!" It was as if someone plunged a dagger in my heart.

The major tweak aims to move better quality content to the top of Google's search rankings. The changes will affect 12% Google's results [sic], the company said in a blog post late Thursday.

I feared time and Google had caught up with me.

It all started on the night of February 17th. It was a dark and stormy night, as I recall. I began searching for an update on the case of Roy Willard Blankenship. He had been scheduled to be executed by the people of Georgia that evening. I was surprised that I could find no news about whether or not the execution had been carried out.

It all started on the night of February 17th. It was a dark and stormy night, as I recall. I began searching for an update on the case of Roy Willard Blankenship. He had been scheduled to be executed by the people of Georgia that evening. I was surprised that I could find no news about whether or not the execution had been carried out.

I checked again the next morning. Still no news then or later that day. The next day I saw bits of information that his execution had again been stayed, though no details were forthcoming. (His execution had been previously stayed based on the expiration date of the lethal chemicals Georgia planned to inject into him.) To this day, a hard-target search (of every gas station, residence, warehouse, farmhouse, henhouse, outhouse and doghouse) on Google reveals no evidence of why Blankenship's execution was stayed on the 17th.

I find that curious.

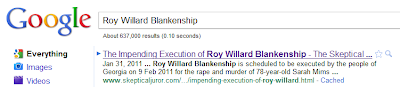

While the impending execution of anyone in this country is serious business, I must return to the point of this post. While searching for information about Roy Willard Blankenship, I simply typed Roy Willard Blankenship into Google. I was admittedly astonished and giddy to see that my post The Impending Execution of Roy Willard Blankenship was #2 in the listings. It would later rise to #1 in the listings.

I'm somebody now! Millions of people look at this book everyday! This is the kind of spontaneous publicity - your name in print - that makes people. I'm in print! Things are going to start happening to me now. -- Navin R. Johnson

I've known for a long time that if one types Skeptical Juror into Google, the first ten pages or so are filled with hits to this august blog. That is to be expected since that two-word phrase is so rarely used elsewhere in polite society.

It was therefore with great trepidation that I typed Roy Willard Blankenship into the search field this morning. Glory Be! Google's new search algorithm still lists my post as #1 out of 637,000 posts. I offer proof of that below.

In reality, there is no joy in Mudville. That top-ranked post contained little original content. I mostly cut and pasted from the 11th Circuit Court decision in Blankenship v. Hall. Furthermore, I simply announced that I would stand mute while we put another of our citizenry to death.

I know also that, had I been using another blog tool when I wrote my post, I would be buried somewhere deep, deep, deep in that list of 637,000 hits. I use Blogger though, and Google owns Blogger, and Google's search algorithm provides undue weight to Blogger posts. If one were to search for Roy Willard Blankenship in Bing, for example, the first hit would be the 11th Circuit Court decision itself.

That's probably a more appropriate top find, given they wrote the decision and I merely cut and pasted from it. Out of curiousity, I began clicking through the Bing search pages to see where my post was listed. I gave up after 50 pages.

There's a lesson in here somewhere. It has something to do with humility and humble pie, and an ability to laugh at oneself. It's also a reminder that I have yet to help free a single innocent person. Even in the cases of Byron Case and Michael Ledford, where I am directly involved, we're working on two-year plans that recognize long odds.

This is not work for the impatient or those who are faint of heart. There is no hope for immediate gratification. Still I choose to be optimistic about my work, our country, and our future. I like my work, I love my wife, and I am a lucky man. I'll leave it to Google and Bing to settle on the proper ranking of my blog posts.