Bees gotta buzz, something's gotta something, and prosecutors gotta prosecute. That was going to be my clever introduction to this august post in which I planned to vent against prosecutorial misconduct. All I needed was a quick Google search to figure out what followed "Bees gotta buzz," and I'd be off to the races. Instead I'm left with another mixed metaphor that stinks like fish in a barrel.

It took me only a couple minutes to find the source of the quote I was going to leverage. It comes from Annie Dillard and her novel Pilgrim and Tinker Creek.

There's a Wikipedia article about the book, from which I obtained the cover image and to which I've hyperlinked the title. It is from that Wikipedia article that I learned once again how wrong I can be. I now excerpt from that article:

Fish gotta swim and birds gotta fly. Prosecutors, it seems, gotta do one horrible thing after another.

It is not my intention to equate prosecutors with insects. But, like any other collection of humans, prosecutors can be either good, bad, or ugly, to borrow from another masterpiece.

It is bad prosecutors of whom I will be writing, the ugly ones, the ones that gotta do one horrible thing after another.

It is bad prosecutors of whom I will be writing, the ugly ones, the ones that gotta do one horrible thing after another.

Over the last decade, I've come to realize that prosecutors are the primary cause of wrongful convictions. Certainly there are enough wrongful convictions to go around, some to attribute to the police, some to attribute to mistaken identity, some to attribute to insufficiently skeptical jurors. But the primary cause of wrongful convictions, I now maintain, is, far and away, those prosecutors that gotta do one horrible thing after another.

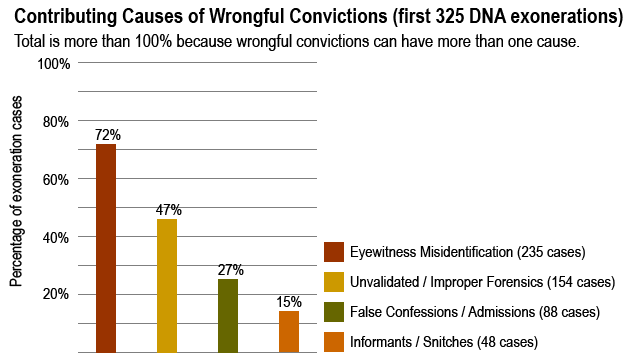

The (national) Innocence Project, long long ago in a place far far away, used to report that prosecutorial misconduct is responsible for 25% of wrongful convictions. I state that not as a fact, but as a recollection, and concede I might be wrong. I've checked again just now, and I find only a handy dandy colorful bar chart, which I've embedded below for your viewing convenience.

Well I guess I'm wrong about claiming most wrongful convictions stem from prosecutorial misconduct. Even the (national) Innocence Project, which keeps records on such matters, and which is the most respected name in such matters, cannot find sufficient evidence of prosecutorial misconduct to justify even a tiny bar in in its colorful bar graph. My only hope for neurological redemption is in the note that the (national) Innocence Project adds beneath its bar chart.

Well I guess I'm wrong about claiming most wrongful convictions stem from prosecutorial misconduct. Even the (national) Innocence Project, which keeps records on such matters, and which is the most respected name in such matters, cannot find sufficient evidence of prosecutorial misconduct to justify even a tiny bar in in its colorful bar graph. My only hope for neurological redemption is in the note that the (national) Innocence Project adds beneath its bar chart.

It suddenly seems that the (national) Innocence Project seemingly did find at least one possible case of government misconduct that led to a wrongful conviction, but they chose not to quantity how many. Maybe my memory was not so faulty after all. Maybe they did indeed previously claim that 25% of wrongful convictions stemmed from prosecutorial misconduct, but they now choose to mask that number, as a convenience to the readers.

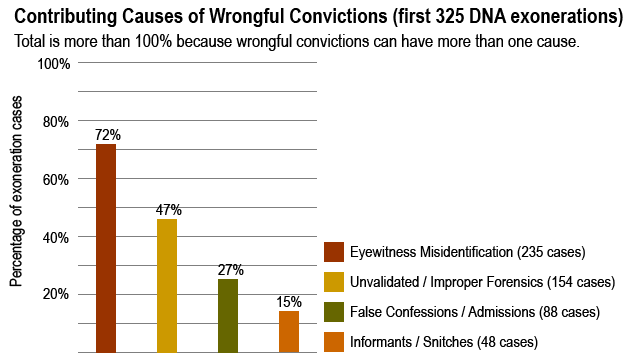

I now turn to the Death Penalty Information Center, an organization and web site not so politic in its quantified reporting. It offers its own handy dandy colorful bar chart and its own textual description, which I embed below for your viewing convenience.

As The Skeptical Juror, and as this site's duly elected contrarian, I take a third position. I suggest that both sites are understating the contribution of prosecutorial misconduct to our country's abysmal rate of wrongful conviction. You might therefore anticipate that I am not done pontificating on the subject.

Stay tuned.

Pilgrim at Tinker Creek is a 1974 nonfiction narrative book by American author Annie Dillard. Told from a first-person point of view, the book details an unnamed narrator's explorations near her home, and various contemplations on nature and life. The title refers to Tinker Creek, which is outside Roanoke in Virginia's Blue Ridge Mountains. Dillard began writing Pilgrim in the spring of 1973, using her personal journals as inspiration. Separated into four sections that signify each of the seasons, the narrative takes place over the period of one year. [...]

A passage in the second chapter of the book describes a frog being "sucked dry" by a "giant water bug" as the narrator watches; this necessary cruelty shows order in life and death, no matter how difficult it may be to watch. The narrator especially sees inherent cruelty in the insect world: "Fish gotta swim and birds gotta fly ... insects, it seems, gotta do one horrible thing after another. I never ask why of a vulture or a shark, but I ask why of almost every insect I see. More than one insect ... is an assault on all human virtue, all hope of a reasonable god."I thereby stumbled into an even more clever introduction to this august blog post, though the time for introduction is nigh past. That bus has sailed, as the Skeptical Spouse once so wisely said. So I'll get on with it.

Fish gotta swim and birds gotta fly. Prosecutors, it seems, gotta do one horrible thing after another.

It is not my intention to equate prosecutors with insects. But, like any other collection of humans, prosecutors can be either good, bad, or ugly, to borrow from another masterpiece.

Over the last decade, I've come to realize that prosecutors are the primary cause of wrongful convictions. Certainly there are enough wrongful convictions to go around, some to attribute to the police, some to attribute to mistaken identity, some to attribute to insufficiently skeptical jurors. But the primary cause of wrongful convictions, I now maintain, is, far and away, those prosecutors that gotta do one horrible thing after another.

The (national) Innocence Project, long long ago in a place far far away, used to report that prosecutorial misconduct is responsible for 25% of wrongful convictions. I state that not as a fact, but as a recollection, and concede I might be wrong. I've checked again just now, and I find only a handy dandy colorful bar chart, which I've embedded below for your viewing convenience.

Contributing causes confirmed through Innocence Project research. Actual numbers may be higher, and other contributing factors to wrongful convictions include government misconduct and bad lawyering.In other words, results may vary, contents may have settled during shipping.

It suddenly seems that the (national) Innocence Project seemingly did find at least one possible case of government misconduct that led to a wrongful conviction, but they chose not to quantity how many. Maybe my memory was not so faulty after all. Maybe they did indeed previously claim that 25% of wrongful convictions stemmed from prosecutorial misconduct, but they now choose to mask that number, as a convenience to the readers.

I now turn to the Death Penalty Information Center, an organization and web site not so politic in its quantified reporting. It offers its own handy dandy colorful bar chart and its own textual description, which I embed below for your viewing convenience.

Many factors contribute to wrongful convictions, and it is no different in capital cases. But the most recent data from the National Registry of Exonerations points to two factors as the most overwhelmingly prevalent causes of wrongful convictions in death penalty cases: official misconduct and perjury or false accusation. As of May 31, 2017, the Registry reports that official misconduct was a contributing factor in 571 of 836 homicide exonerations 68.3%, very often in combination with perjury or false accusation, which also was a contributing factor in 68.3% of homicide exonerations.Holy conflicting data, Batman! We now have evidence that official misconduct justifies either no bar in a colorful bar chart OR an 80% bar in a colorful bar chart. I suspect it might be difficult to rationalize those two results as consistent. Instead, I suspect it more likely that one site is downplaying the problem of official misconduct, for whatever reason, and/or the other site is exaggerating the problem, for whatever reason.

As The Skeptical Juror, and as this site's duly elected contrarian, I take a third position. I suggest that both sites are understating the contribution of prosecutorial misconduct to our country's abysmal rate of wrongful conviction. You might therefore anticipate that I am not done pontificating on the subject.

Stay tuned.