DRAFT

August 6, 2012

The Honorable Robert F. McDonnell

Governor of the Commonwealth of Virginia

In the Matter of Michael J. Ledford, Petitioner

Petition for an Absolute Pardon

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Michael Ledford is serving the twelfth year of a fifty-year sentence for arson and the first-degree murder of his one-year-old son. He pleaded not guilty and has maintained his innocence ever since. He has expended all his appeals, including his one appeal based on actual innocence. A recent independent re-examination of the evidence in his case has determined that the fire resulted not from arson, but from a seriously overheated electrical circuit. Since Michael Ledford's only remaining avenue for relief is executive clemency, he asks that you carefully consider this petition for absolute pardon.

On October 10, 1999, Petitioner Michael Ledford left his apartment to run errands. His wife and his one-year-old son were asleep in separate bedrooms at the rear of the apartment. As he departed, Michael turned on a nearby table lamp using the wall switch near the entry door. That simple, innocent act triggered an electrical fire within the deteriorating electrical system.

Other residents of the Highland Hills Apartments had recently been having problems with their electrical systems. In an adjacent building, a sewing machine motor dragged and a nightlight refused to work. The tenant noticed that the electrical outlet was "very warm." The tenant notified the management. The management had the outlet replaced.

In another apartment, another outlet had become hot to the touch. The tenant notified the management. The management had the outlet replaced.

In one of the two apartments directly above the Ledford apartment, the tenant experienced problems with a kitchen outlet. Being young and self-confident, he replaced the outlet himself.

At least one of the outlets in the Ledford apartment had been deteriorating for a while. That outlet, however, was located behind the sofa, and no one noticed that it was overheating. The Ledford family and friends did notice that a table lamp had started acting up. Its switch seemingly worked only intermittently. Everyone learned to use the wall switch to control the lamp. It was that wall switch Michael flipped to the ON position as he left to run his errands.

A wall outlet is shown below. It is the outlet that powered the bothersome table lamp. It is the outlet controlled by the wall switch near the door.

There is no doubt that the wiring inside that outlet had burned. The smoke streaks radiating from the perimeter of the outlet and its faceplate provide evidence of a fire within. Even the insurance investigator, an adverse party to Michael's defense and the only person to actually examine the wiring, conceded that it had burned. The insurance investigator, however, assured the jury that the wiring had been a victim of the fire rather than its cause. The insurance investigator assured them that the wiring inside burned only when the fire outside swept over the outlet.

While there is no doubt that the wiring inside the outlet was burned, it could only have burned because it overheated itself from within. The only possible alternative, that it burned as fire swept past, is impossible. No fire did sweep past that outlet. The area behind the couch was spared by the fire, as shown in the image below.

The composite image shows the relative positions of the couch and the wall outlet. The wall outlet would have, of course, been facing the back of the couch, rather than facing away from it as shown. It is the relative positions of the couch and outlet that are of importance.

The composite image shows clearly that the front of the couch was seriously burned and charred. The image shows with even greater clarity that the area of the couch nearest to the electrical outlet was unburned. There was no fire behind the couch. Fire did not sweep across the face of the outlet. The burned wiring within the outlet did not result from an external heat source.

Though the composite image is compelling by itself, one does not need to rely on it alone. The same conclusion is unavoidable by looking just at the faceplate. It is not melted. It is covered with soot from the fire within, but it is not in any way melted. An external heat source powerful enough to burn the internal wiring would certainly have melted the plastic faceplate.

The burned wiring within the outlet was hardly the only evidence of an overheated electrical circuit. Both the lamp cord and the extension cord lost their prongs when they were unplugged by the investigators. Neither plug showed any substantial damage from external heating. Instead they heated from within sufficiently that they softened, their connections failed, and their prongs separated as the plugs were pulled free.

The light bulb in the table lamp exploded. This is exceedingly rare. Light bulbs are surprisingly durable, designed as they are to withstand the several thousand-degree temperature of their white-hot filaments. Even when heated by a raging fire, light bulbs merely soften and sometimes bulge towards the heat source. Light bulbs can burst if cooled too quickly when firefighters hit them with water, but the fire in the Ledford living room self-extinguished. Not a drop of water was used to extinguish it. Nor did anyone bump or bang the bulb, at least not with sufficient authority to knock the lamp over; the investigators' photos show the lamp still standing in its original position.

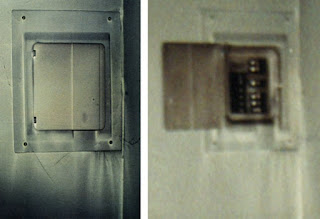

Normally, one would expect an overheating circuit to be interrupted by a circuit breaker. The evidence of an overheated, unprotected circuit unfortunately extends all the way to the circuit breaker box. Smoke streaks around the service panel and heavy sooting inside indicate that a fire burned or smoldered within that breaker box.

One breaker actually showed a burn mark on its handle.

The same breaker shows startling evidence of an egregiously unsafe repair. Rather than replacing the breaker after a presumed earlier problem, maintenance personnel merely glued plastic strips over the top of it.

A sooted spider web connects the plastic strip and its oozing adhesive. The spider web is evidence that the improperly repaired breaker had been deteriorating for some time. The spider web is evidence also that a cheap, improper repair eventually cost an infant child his life and the father his freedom.

The crudely patched circuit breaker is not the only egregious code violation revealed by the investigators' photos. Shockingly, the smoke detector was installed without an electrical box. It was supported only by a couple of plastic anchors and (later) its wires, which also are burned.

Of even greater concern than the missing electrical box is what appears to be a severed electrical cable visible in the overhead. Given the ragged end of the exposed cable, and given the equally ragged edge of the hole, it seems as if the electrical cable may have been severed when someone carelessly cut the hole to install the smoke detector.

The missing electrical box, the crudely cut hole, and the apparently severed cable suggest that the box was installed during a retrofit program, one that focused on minimizing cost rather than insuring safety.

The evidence of an electrical fire inside the Ledford apartment is substantial and compelling. Michael was not convicted because the investigators found no evidence of an electrical fire. They found plenty. Nor was Michael convicted because the investigators found some evidence of arson. They found none, none whatsoever. Michael was convicted instead because he confessed.

Though Michael quickly recanted his confession, and though his confession shows the classic hallmarks of being false, Michael did confess. Juries find confessions compelling, even if the confession has been recanted, even if the confession stands in stark contrast to all evidence at the scene.

Juries simply do not understand that false confessions are common.

The Innocence Project explains that in approximately 25% of all DNA exonerations, the person exonerated had either confessed or provided an incriminating statement. Studies conducted since Michael's conviction show that most people, more than 50%, will falsely confess when subjected to interrogation techniques similar to those used on Michael Ledford.

Virginia Governors have a noble history of granting clemency when a person has been proven innocent and when no other relief is available.

In 1989, Governor Gerald Baliles pardoned David Vasquez, though Vasquez had falsely confessed to the rape and murder of Carolyn Jean Hamm. Governor Baliles believed Vasquez to be innocent, so he set Vasquez free.

In 2000, Governor James Gilmore granted Earl Washington, Jr. an absolute pardon, though Washington had falsely confessed to the rape and murder of Rebecca Lynn Williams. Governor Gilmore believed Earl Washington was innocent, so he set Washington free.

In 2009, Governor Tim Kaine granted conditional pardons to three of the Norfolk Four, though they had each falsely confessed to the rape and murder of Michelle Moore-Bosko. Governor Kaine suspected the three were likely innocent, so he set them free.

Because Michael Ledford was in no way responsible for the fire that took the life of his one-year-old son, and because he has no alternative avenue for relief, he prays that you will grant him an absolute pardon.