The case against Francis Elaine Newton seemed pretty convincing. At least it seemed so if you allowed the people of Texas explain it, and you were courteous enough to not ask any troublesome questions.

According the people of Texas, Frances Elaine Newton purchased a $50,000 life insurance policy on her husband Adrian and forged his name to complete the deal. Frances also purchased a separate $50,000 life insurance policy on her 21-month old daughter, Farrah. Frances made herself the beneficiary on each policy.

Less than a month later, on 7 April 1987, Frances shot her husband in the head and her daughter in the chest. Both died on the scene. Frances also shot her 7-year-old daughter son, Alton, in the chest. Alton also died on the scene.

Frances then drove to her parents’ burned out, abandoned house and hid a blue cloth bag containing a Raven Arms .25 automatic pistol. Frances had stolen the pistol from her boyfriend’s dresser. It turns out Adrian and Frances Newton were insignificant others. Both were seeing someone else.

The police quickly recovered the weapon, tagged it, and tested it. It turned out to be the murder weapon. They tested Frances’ clothes for gunshot residue and found nitrates on the hem of her skirt.

The people of Texas had all they needed to send someone to the non-electric gurney. They had means (the Raven Arms .25 pistol and the gunpowder residue on her skirt), they had motive (the insurance policies, one with a forged signature), and they had opportunity (Frances did not have a solid alibi for the time of the shooting.) They had so much, they didn’t even need a snitch. Instead, they secured a conviction by appointing Ron Mock as Frances Newton’s attorney.

<<>>

Ron Mock wasn’t just a bad attorney. He was the king of bad attorneys. For a while, prisoners and attorneys referred to one section of death row as “The Mock Wing” because it was so heavily populated with his clients. At least 16 of them found their way to death row. Not even once did Ron Mock ever gain an acquittal in a capital murder case.

There was no need for Ron Mock, however, to suffer for the failings of his clients. "I drank a lot of whiskey. I drank whiskey with judges. I drank whiskey in the best bars. But it never affected my ability. It never affected my performance.” The cozy relationship with the Texas judges caused Ron to be selected for death penalty cases more frequently than any other attorney in the state. Unlike most court appointed attorneys in Texas, Ron Mock seemed to have money to burn. In the 1980s, he made over $120,000 per year. He claimed he stopped handling death penalty cases because the money wasn’t good enough. The fact that he was suspended multiple times by the Texas Bar may have had something to do with it as well.

"I had nothing, really, to work with other than Frances saying that she didn't do it," he would later tell a reporter. In pre-trial preparation (for lack of a better word), Mock filed no motions, interviewed no witnesses, failed to submit a subpoena list for defense witnesses, and met only briefly with his client.

Francis Newton asked the court to replace him. The court refused. After her family spent time rounding up money for a private attorney, the court did allow the potential new attorney the opportunity to question Ron Mock.

"You knew the name of Ms. Newton's cousin [who could provide exculpatory testimony] the day you read the State's file. Why didn't you go out and talk to her?" >> I tell you I'm a lawyer, I'm not an investigator.

"Can you give me the name of any witnesses, either state or defense witnesses in this case, that you have talked to?" >> Not off the top of my head, no, I can't.

When asked how many times he met with his client, Mock testified that during the 18 months he had represented Newton, he met with her "three, maybe four times" for "probably one hour each." He explained that his knowledge of the case consisted primarily of information provided by the prosecution.

After Mock’s stellar performance in the witness box, the court agreed Newton could replace Mock with her newly discovered private attorney, but that no delay would be granted to allow the new attorney time to prepare. They were in the midst of voir dire, after all.

Newton decided to stick with Ron Mock. She was executed on September 14, 2005.

<<>>

"I had nothing, really, to work with other than Frances saying that she didn't do it.” -- Ron Mock speaking of Frances Elaine Newton

<<>>

Let’s consider whether Ron Mock had nothing other than Frances’ proclamation of innocence. Let’s first consider the insurance policies.

There’s no doubt that the purchase looks bad, particularly in light of Frances forging her husband’s signature. Frances claimed she forged the signature to prevent husband Adrian from knowing she had set money aside for the payments. It seems a bit weak. Consider, however, some other aspects of the insurance purchase.

Frances did not purchase life insurance for seven-year-old daughter son Alton, though Alton was killed along with husband Adrian and 21-month-old Farrah.

Frances purchased $50,000 worth insurance on her own life, though she obviously did not kill herself. There is little correspondence between the people for whom she purchased life insurance and the people who were murdered.

Frances did not make herself the sole beneficiary on her husband’s and her daughter’s children's policies. Frances was the primary beneficiary and her mother was a secondary beneficiary.

While Frances and Adrian were indeed having marital problems, Texas provided no motive for Frances killing her daughters children. Frances could have just as easily insured Adrian for $100,000 and spared her two daughters children.

But wait, as they say when they’re trying to sell you something, there’s more.

Frances did not seek out an insurance agent and ask to purchase life insurance. An insurance agent found her. State Farm agent Claudia Chapman approached Frances in September of 1986 to purchase automobile insurance. Frances didn’t ask to add life insurance, Chapman brought the subject up and encouraged Frances to add that coverage. Chapman tried to sell the deal by pointing out the life insurance had the added benefit of acting as a savings account. Frances did not at that time purchase the insurance.

Two months before the murders, however, three of her cousins died in a house fire. It was a financial tragedy piled on top a personal tragedy, since the family did not have the money to pay for the funerals. Frances’ cousins, in fact, died in the burned-out, abandoned house where she later placed the bag that held the gun that convicted her.

After that fire, Frances’ father advised her and her siblings to prepare for the future, in part by purchasing life insurance. It was only then, after having been pitched by Claudia Chapman, after having lived through the death of her cousins, and after being advised by her father, that Frances purchased the life insurance.

Somehow, the jurors were never informed of all the circumstances surrounding Frances’ purchase of life insurance. Somehow, the state portrayed a perfectly innocent act as a ruthless and heartless plan to murder one child for $50,000 and another one for free.

<<>>

There’s also the matter of Frances’ alibi. Let’s consider the timeline for the tragic evening of 7 April 1987.

Sometime between 5:30 and 6:00 PM, Sterling Newton came home. Sterling was husband Adrian’s brother. He was living with Frances and Adrian. Frances asked brother-in-law Sterling to leave for a while because she wanted to speak with Adrian alone about their marital problems. Adrian nonetheless stayed for an hour to an hour and a half before leaving.

At approximately 6:45 PM, Ramona Bell called. Bell was husband Adrian’s girlfriend. Adrian and Bell spoke for approximately fifteen minutes.

At approximately 7:00 PM, Adrian told Bell he was tired and would be going to bed. He didn’t plan to do so, however, until Frances left. According to Bell, Adrian didn’t trust Frances.

Between 7:00 and 7:15 PM, Alphonse Harrison called to speak with his friend Adrian. Frances answered and put him on hold. After 45 minutes of being on hold, Alphonse hung up.

Between 7:00 and 7:30 PM, Frances arrived at the home of her cousin Sondra Nelms. Frances asked cousin Sondra to come back to her apartment and continue the visit there. As the two were leaving in Frances’ car, cousin Sondra watched Frances remove a blue bag from her car and put it inside the abandoned house next door.

Between 7:45 and 8:00 PM, Frances and cousin Sondra arrived back at the Newton apartment. According to Nelms:

“Immediately upon opening the door, the phone rang. Frances answered the phone and stated ‘I think he's asleep, I'll see if I can wake him.’ At this point, all Frances could see was a sheet over Adrian's lower torso. Neither of us could see his upper torso. As Frances walked around the couch and saw his upper torso, she immediately screamed and bolted to the children's bedroom. Frances began to frantically scream uncontrollably. I could not calm her down enough to elicit the apartment's address. … I know in my heart that after watching the reaction of Frances upon discovering her husband and children, there is absolutely no way she had any involvement in their deaths."

At 8:27 PM, Harris County Sheriff’s Deputy R. W. Ricks was dispatched to the Newton apartment. Outside, he met Frances Newton and her cousin Sondra Nelms. Inside he discovered the bodies of husband Adrian (shot once in the head), 7-year-old daughter son Alton (shot once in the chest), and 21-month-old daughter Farrah (shot once in the chest.) He found no signs of forced entry or struggle.

Sandra Nelms lived at 6524 Sealy Street, Houston, Texas.

Frances Newton lived at 6126 West Mount Houston Road, Houston, Texas.

According to Bing, the distance between the two residences is 5.3 miles. The nominal driving time is 13 minutes. Assuming Frances arrived at her cousin’s house no later than 7:30, as the State concedes, and assuming she made the trip in 10 minutes rather than 13, Frances left her house no later than 7:20. Assuming Adrian was alive at 7:00 PM, as the State concedes, then Frances had a 20 minute window of opportunity to kill her husband and her two daughters children.

Sometime during that 20 minute window, Adrian’s friend Alphonse Harrison called, was put on hold by Frances, and never managed to speak with Adrian.

It doesn’t look good for Frances.

However …

The people of Texas knew, absolutely knew of an ear-witness living in a nearby apartment. On the night of the shooting, neighbor Clive Adams told Officer J.G. Salinas that he heard a gunshot around 7:30 PM, when everyone concedes that Frances was not at the apartment. Somehow, the jury never heard from Clive Adams. Neither the prosecution nor the defense called him as a witness.

<<>>

Let’s consider next the gunshot residue on the hem of Frances skirt.

On April 8, 1987, the day after the murders, Frances accompanied Detective Michael Parinello during a search of her apartment. She pointed out the clothing she had worn the day of the murders. Detective Parinello collected the clothing and brought it to the crime lab to test for gunpowder residue. A chemist testified that the long skirt contained nitrites consistent with somebody having shot a pistol while holding it close to the lower front area of the skirt.

Perhaps the jury should have found that testimony suspicious all by itself. It paints a picture of a shooter bending over so far and placing the gun so near her ankles that the gunpowder residue ends up only on the hem of the long skirt. Presumably all shots would have been from this position, lest residue land elsewhere on her skirt. Despite that awkward position, the State would have the jurors believe that Frances killed three people with three shots. That’s good shooting indeed, from an extremely awkward position.

Even if the jurors were to accept the alleged shooting position, it leaves unexplained the absence of residue on the Frances’ long sleeve sweater.

And even if the jurors accepted the alleged shooting position and were untroubled by the absence of residue on the long sleeve sweater, that would still leave unexplained the absence of gunshot revenue on Frances’ hands. Just hours after the murders, law enforcement performed an atomic absorption test on Frances’ hands. The tests were negative for gunshot residue.

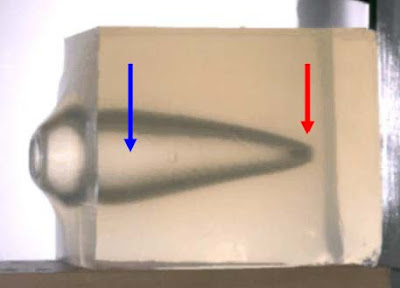

Not only should there have been gunshot residue on Frances and her clothing, if in fact she actually killed her husband and daughters children, there should have been blood, particularly from husband Adrian. Adrian was shot in the head, and head wounds generate backspatter. Blood and other disturbing matter is ejected out of the entry wound, travels back along the bullet path, and lands on people, clothes, and guns within six feet of the wound. The backspatter is particularly pronounced when the bullet does not exit, as it did not exit from husband Adrian’s head. The backspatter is particularly voluminous when the gun was pushed up against the head when fired, as it was pushed up against husband Adrian’s head.

Adrian was killed execution style as he lay sleeping on the living room couch. The children were also shot at close range, probably after the husband was killed. Blood apparently dripped from the shooter as the shooter moved down the hall and into the children’s bedroom. Neither the prosecution nor the defense apparently felt it was important for the jury to learn of the trail of blood that dripped from the shooter.

Despite the backspatter and other blood all over the floor, the police found zero blood on Frances’ person or clothing, nor did they find any blood or brain matter on the gun retrieved from the burned out house. The prosecution cannot claim that Frances washed the blood from her clothes, since that would have washed the nitrates away. Nor can the prosecution claim that she disposed of her bloody clothes, since they were claiming that nitrates were found on the skirt she was wearing that night.

The police found no blood in Frances car and found no evidence of someone washing away blood in the house. In summary, the presence of gunshot residue on the hem on Frances’ long skirt is absolutely inexplicable in light of the lack of gunshot residue elsewhere, and in light of the lack of blood anywhere on Frances’ person or clothes.

The nitrate evidence is better explained by young victim Farrah’s travels that day. During the day of the murders, twenty-month-old Farrah Newton stayed with her uncle while Frances worked. It turns out the uncle maintained a large garden and used a corresponding amount of fertilizer. Fertilizer contains nitrates, as do cosmetics, tobacco smoke, and urine. Farrah reportedly came into contact with fertilizer at her uncle’s house and apparently transferred a trace to her mother’s skirt.

The trace of nitrates that helped Texas kill Frances Newton may have been unintentionally planted there by her own daughter.

<<>>

There’s no question that three member of the Newton family were shot and killed that night. So, if Frances didn’t kill them, who did? Frances argued that a drug dealer may have. She told the police that Adrian had a drug habit and owed his dealer $1500. (That might help explain why she was reluctant to tell him that she had enough money to make payments on the new life insurance policies.) Adrian’s brother Terrance not only corroborated Frances’ tale of a drug dealer and a debt, he told the police where the dealer lived. During trial, even Ron Mock knew enough to ask Sheriff’s Officer Frank Pratt about the dealer.

"To your knowledge, was the alleged drug dealer ever interviewed by anyone in connection with this case?" >> No.

Husband Adrian was a drug user and a small-time drug pusher. According to Frances, she talked to Adrian about their marriage and his drug problems just before she left the apartment that night. Adrian claimed he was no longer using drugs. Frances was skeptical. While Adrian was watching television, Frances opened the cabinet where Adrian kept his stash. There she found a Raven Arms .25 automatic pistol. She recalled a conversation earlier in the day between husband Adrian and brother-in-law Sterling about some trouble they had been in. She didn’t want the gun in the house, removed it, put in a duffel bag and took it with her to her cousin’s house. There, in full view of her cousin, without trying to hide anything from her, Frances removed the bag from the car and placed it in an abandoned house belonging to parents.

Just barely one day after the murder, just before 1:00 AM on April 9, 1987, an anonymous female caller to the Harris County Sheriff’s Department and claimed she had noticed a red pickup truck at the scene of the murders on April 7. She claimed the driver was a black male approximately 30 years old. She provided the license number. The police later traced that number, but not further follow up on that lead.

<<>>

That of course brings us to the gun. How could the gun that Adrian removed from the Newton apartment be used to kill the Newtons unless Frances used that gun to do so before she left?

Good question. The answer is, it couldn’t.

Another gun, however, may have.

Three-card Monte is the game for suckers in which a con-man challenges the mark to pick the Queen of Hearts, the Ace of Spades, or some other seemingly impressive card from the three alternately picked up and dropped on a table. (“Table” is a generous word in this case. The platform is frequently a cardboard box to allow rapid getaway from outraged bettors or pesky police.) It’s a winning game for the con-man, who knows what’s going on, and a losing game for the mark, who is kept in the dark and/or misinformed by shills assisting in the scam.

In the Newton case, there were at least two, and perhaps three Raven Arms .25 automatic pistols floating around.

Gun number 1 is obviously the gun that Frances placed in the abandoned house next to her cousin’s house. She placed the bag carrying that gun in the house while in full sight of her cousin Sondra, rather than secretly. Later that evening, when cousin Sondra was interviewed by homicide detective Michael Talton, cousin Sondra told him of the bag and escorted him to the abandoned house. There, Talton, recovered the bag and found the gun inside. Talton testified that Frances told him she put the weapon there because husband Adrian had told her he was expecting trouble and that she did not want the strange gun in her house.

The pistol was turned over for ballistics testing the next day. Testing that same day established that the gun fired the bullets recovered from the bodies. The results came in while Frances was still at the police station, yet they did not arrest her then and there. They did not arrest her that day, or the next, or that week, or the next. Despite the seemingly conclusive proof of her guilt, the police did not arrest Frances Elaine Newton until two weeks later, on April 22, 1987. Even then they did not arrest her based on the physical evidence. They arrested her because she and her mother applied to collect the insurance money.

When shown the gun at trial, the officers testified only that it “appeared similar” to the one recovered and tested. They did not identify it by its serial number or by any distinguishing characteristics. If they so testified because they failed to record the serial number, that’s bad. If they so testified because the serial number would be troublesome to the State’s case, that’s obviously worse. Either way, the failure to record and identify the weapon by its serial number is a serious and suspicious shortcoming of the State’s case.

Gun number 2 was revealed by Sheriff’s Sgt. J.J. Freeze. He told both Frances and her father that police had actually recovered two guns. Apparently, affidavits from two police investigators also allude to the recovery of a second gun.

In case you doubt the word of Frances, her father, and two unidentified police investigators, perhaps you’ll accept the word of an assistant district attorney. Not long before Frances’ execution, Assistant DA Roe Wilson confirmed to a Dutch reporter that “police recovered a gun from the apartment that belonged to the husband,” but added that it “had not been fired, it had not been involved in the offense. … It was simply a gun [he] had there, so there is no second-gun theory.” Wilson later claimed to have “misspoken.”

It’s fortunate that Wilson merely misspoke, since prosecutors never revealed the existence of a second gun to the defense. Had Wilson not “misspoke,” had prosecutors actually withheld such exculpatory information, that misconduct could be the basis for yet another appeal or another plea for clemency.

During trial, Freeze was conveniently vague in his recollection of the second gun. "I believe we talked about two pistols. I know of one for sure, and there was mention of a second one that Ms. Newton had purchased earlier.

Gun number 3 was uncovered by Newton’s appellate attorney and law students from the University of Houston. Two police investigators affirmed tracing guns in connection with the Newton murders. Officer Frank Pratt told one of the students that he was assigned a gun found in the abandoned house, which he traced to a purchase by Frances’ boyfriend at a local Montgomery Ward store. He also discovered that the boyfriend had purchased a “second, identical gun.” Pratt did not follow up on that “second, identical gun” because “he felt there was no need to do so.”

Detective M. Parinello traced yet another firearm associated with the case to a purchase from Rebel Distributors in Humble, Texas. According to Detective Parinello, that pistol also ended up in the hands of Frances’ boyfriend.

Frances’ appellate attorneys asked the Harris County Sheriff’s Department to provide all records relating to all the guns associated with the Newton murders. The department of course declined.

It’s not particularly surprising if Harris County lost one or two guns. In 2004, the year before Frances was executed, the Houston chief of police asked Texas to delay all executions based on evidence processed by the Harris County crime lab. Hundreds of previously missing evidence boxes pertaining to more than 8,000 criminal cases had recently been discovered.

<<>>

So there you have it. Frances Elaine Newton was executed by the people of Texas because she purchased life insurance, had traces of nitrate on the hem of her skirt, and (nearly) surreptitiously moved a gun from her apartment to an abandoned house belonging to her parents. The jury never learned of the ear witness who placed the murder at a time when Frances was not at home. No one involved in convicting or executing her seemed particularly bothered that she did not have gunshot residue on her person or her long sleeve sweater, or that the nitrates could have been something other than gunshot residue. No one seemed disturbed by the absence on blood on her person or her clothing. No one seemed to care that police and prosecutors spoke of one, two, or three weapons, and that they failed to record and track by serial numbers.

I score Frances Elaine Newton at 91. That means I estimate her probability of actual innocence to be 91% and her probability of actual guilt to be only 9%. That number ties her with Johnny Frank Garrett, the only other person I have scored above 90.

Frances was the 110th person executed during Rick Perry’s watch. Perry had by that time served 1,728 days. That works out to one execution every sixteen days of his governorship. Many of those people were probably innocent.